Finding Harriet Jacobs’ Underground Railroad Safe House in Philadelphia

- 1838 Black Metropolis

- Aug 28, 2024

- 6 min read

Updated: Apr 17, 2025

In the Spring of 1842, Harriet Jacobs arrived in Philadelphia. She was met at the docks by a Reverend Jeremiah Durham.

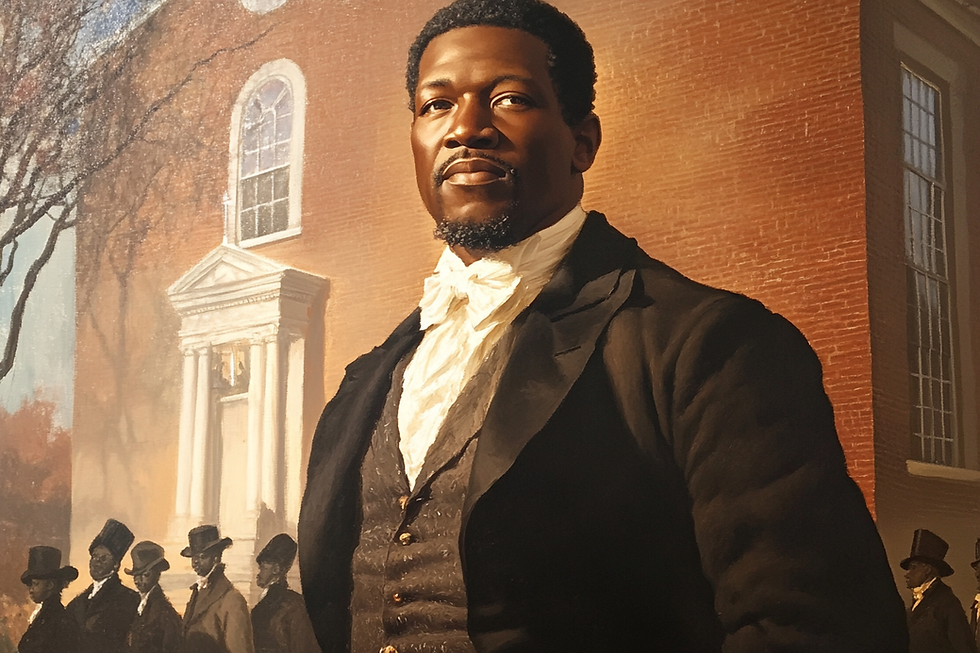

Rev. Durham was a popular minister at Mother Bethel AME, and, as we find is so prevalent with ordinary people in the 1838 Black Metropolis, also an Underground Railroad agent. Someone had told him to meet Harriet Jacobs, a freedom seeker, at the docks. Recognizing her need for rest, Rev. Durham gently persuaded her to stay with his wife and children at his home.

When Jacobs arrived at the Durham home, “Mrs. Durham met me with a kindly welcome, without asking any questions. I was tired and her friendly manner was a sweet refreshment. God bless her! I was sure that she comforted other weary hearts before I received her sympathy.” (Page 243)

Jacobs’ initial intention was to continue to New York as quickly as possible. But due to the concern the Durham family and their extended community showed to her, she stayed five full days in Philadelphia.

During that time, she describes daily life on the street outside the Durham house. “At daylight, I heard women crying fresh fish, berries radishes and various other things. All this was new to me. I dressed myself at an early hour and sat by the window to watch the unknown tide of life.” (Page 246).

Most importantly, it was at the Durham home that Jacobs first met a member of the Vigilance Committee and began to tell her story.

It is this story, the one that unfolded in the living room of the Durham household, for which she is known today. The kindness of the Durhams and the comfort of their home, helped her to open her life to unknown people, and to describe the incredibly harrowing journey to freedom that she eventually documented in her book.

Philadelphia was often the first place freedom seekers could rest safely after journeying north on the Eastern arm of the Underground Railroad.

We need to consider and celebrate the vast number of support workers in the Black community, people like the Durhams - hundreds of people who opened their homes, people who had the skills to help others begin to adjust to a new environment, and people who eventually helped people unpack their trauma.

Many Philadelphia houses from that time period are still standing. So we decided to see if the house still existed. If so, it can be considered an Underground Railroad stop. We imagined that if it still existed, its walls still whisper of community and liberation.

Here are the steps we took to find the house:

Was the Reverend Jeremiah Durham a Real Person?

We turned to discovering if Jeremiah Durham existed in 1838. We found a Jeremiah Durham in the 1838 Census on Barley street.

We then turned to the city directories to find if there were other Jeremiah Durhams in the city. He is the only one between 1838 and 1847. Harriet Jacobs arrived in 1842.

We then validated that Jeremiah Durham existed in the US census. He exists in Philadelphia’s Cedar ward in the 1840 Census.

Validating Jeremiah Durham’s Occupation

Incidents in the Life of a Slave Girl says that Durham was a Clergyman. However, his city directory listings say his occupation was ‘Carter’ in the late 1830s and early 1840s. We wanted to validate that he was a Reverend when Harriet Jacobs arrived.

Durham was indeed the Reverend of Shiloh Baptist Church in the 1840s and because of that, his history is written in The Rise and Progress of Shiloh Baptist. From this book we learn that prior to 1845, which is when he took a full time job at Shiloh, he preached at the church's 11th street location from time to time. Shiloh began in 1841 (see our new page on early church histories). This means that he was publicly preaching during the year that Harriet Jacobs arrived and was most likely known in the community as ‘Reverend’, even though that was not yet reflected in his city directory occupation (Page 62).

Keen eyed readers may wonder how Durham said he was a Methodist in 1838 and then became a Baptist preacher. That process - and the drama surrounding it - are outlined in The Rise and Progress of Shiloh Baptist.

This location was around the corner from his home on Barley street. Shiloh’s first location was on the lot owned by Reverend Absalom Jones, which eventually became the site of the Banneker Institute (Page 12). You can see from the map how close Durham’s house was to Shiloh’s first location.

Which House On Barley Street?

The 1838 Census let us know that he was on Barley street, but we wanted to know the exact house. So first we used the 1860 Hexamer and Locher map to find the current name for Barley, which is now Waverly Street.

Doing a web search we came across a genealogy site called moors-delaware.com. From this site we gained an invaluable clue - a deed of sale.

We then investigated the Philadelphia Land Records to find deed GS: 45: 511.

The deed provides more validations. First, it validates the 1838 Census, where Durham indicated that he had real estate. He was the grantor on the deed - meaning he was selling the home. And the grantee on the deed is Stephen Smith. Smith is identified as a ‘lumber merchant’. This helps us to validate that the Stephen Smith who was grantee (the buyer) is indeed the same Stephen Smith of Beneficial Hall fame. Smith was also an AME minister. In the 1838 census, Durham indicated that he attended Mother Bethel church. These additional points of connection gave us confidence that the deed was for the correct Jeremiah Durham.

The deed also indicated the precise location of the house. “That certain tenement and lot or piece of ground situate on the south side of Barley Street in the said city of Philadelphia, beginning at the distance of 159 ft Westward from the west side of Delaware 10th Street, containing in front breadth of said Barley Street 15 ft and in length a depth southward 62 ft, bounded westward by a lot of Hartman Kuhn, and on the east by the street 18 by 62 ft long called Carolina place, and on the south by a 15 ft wide alley and on the North by Barley Street.” commas added for clarity

We got in touch with the Philadelphia Historic Commission’s Jon Farnham and validated that the house next door, 1018 Waverly, was indeed owned by Hartman Kuhn and that the house that currently exists in the spot indicated by the deed, 1016 Waverly, existed in 1840.

So the house was confirmed. 1016 Waverly was Jeremiah Durham’s House in 1842.

Understanding Harriet Jacob's Experience

So now that we know which house, we can walk the street and imagine what it must have been like for Harriet Jacobs.

Fortunately for us, the street is little changed. And again, another set of fortuitous occurrences, the house has been renovated with respect for its historic touches.

The owners have chosen to keep the original ceiling beams and from the looks of the public pictures, the original floors and stairs.

When we look at this picture, we can imagine Harriet Jacobs, Jane Durham, Rev. Durham and a member of The Vigilance Committee sitting around the fire and hearing Jacobs story for the first time. We think this kind and caring reception was instrumental in helping Jacobs to feel that it would be ok to tell her story to the world.

Sources:

Jacobs, Harriet. 1861. Incidents in the Life of a Slave Girl. History of Women. Boston: Pub. for the Author.

Guinn, Franklin B. 1907. The Rise and Progress of Shiloh Baptist Church. Shiloh Baptist Church. Philadelphia.