A Fresh Look at Francis Johnson, Philadelphia's Musical Magnet

- Tyler Diaz

- Feb 25, 2024

- 10 min read

Updated: Dec 13, 2024

The 1838 Black Metropolis is pleased to welcome intern Tyler Diaz to the team! His insight into Frank Johnson brings this incredible historic figure alive to us in the present in a fresh new way.

I’m Tyler!

I am an electric guitar player, music educator, and musicologist from New York City. As a Mellon Public Humanities and Social Justice scholar at CUNY Hunter College, I have been conducting grant-funded research on the lives of early nineteenth-century Black musicians of Philadelphia.

This research opportunity led me to Antebellum Philadelphia, where I was introduced to one of our nation’s first world-renowned creators of music, Francis “Frank” Johnson.

A Celebrated Personage

I first came across Francis Johnson at the Schomburg Research Library in Harlem where I found a 1983 self-published book by Arthur R. LaBrew titled Studies in Nineteenth Century Afro-American Music.

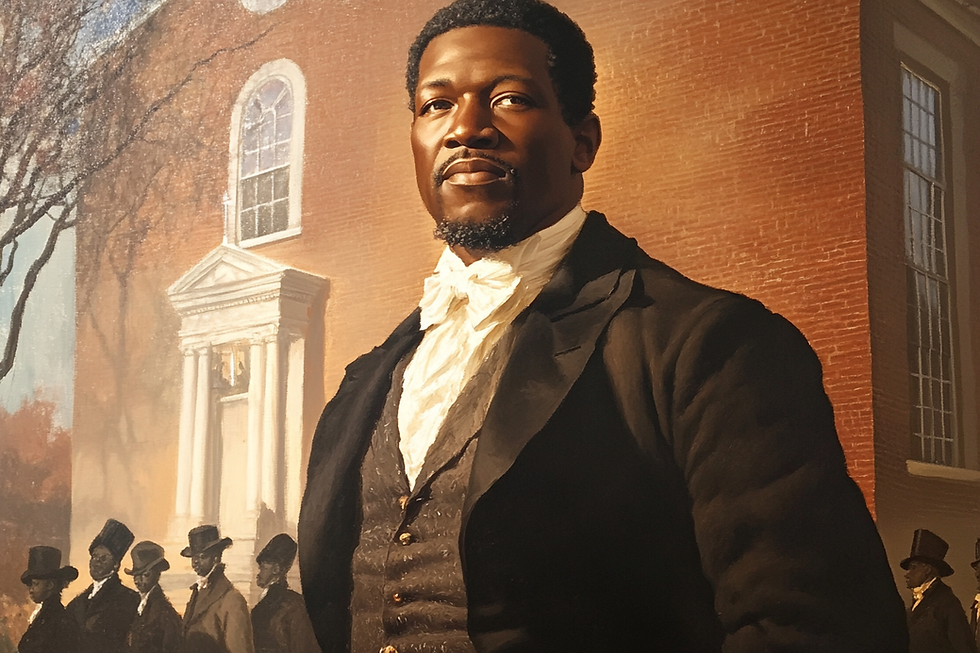

[Frank Johnson, photo courtesy Historical Society of Pennsylvania]

Today, I know there was a large Black music community in Philadelphia and Francis Johnson was at the center of it all. This blog post serves as a brief account of his life and displays how he became “universally respected” and “one of the most celebrated personages of Philadelphia” (Francis Johnson's Obituary in The Public Ledger April 10th, 1844).

Francis Johnson was born in 1792 in Philadelphia, and grew up in St. Thomas Episcopal Church. At an early age he was surrounded by Philadelphia’s Black leaders, like James Forten and Absalom Jones.

At 18 years old, he was known locally as a fiddler while playing at the Exchange Coffee House, the former site of Senator William Bingham’s mansion on Spruce Street between 3rd and 4th.

Sometime during the 1810s, Johnson was introduced to the Keyed Bugle, an immediate predecessor to the trumpet. With the mastery of this new instrument paired with his noted virtuosity on the violin, Johnson began his rise to national acclaim.

Although he likely wrote his first composition “Bingham’s Cotillion” in 1810, a nod to the location of the coffee house, it was in 1818 when Johnson’s earliest known publication was printed: it was his A Collection of new Cotillions. This was the first of a collection of eight Setts that would establish his popularity as a composer.

[Cover page of Francis Johnson’s A Collection of new Cotillions. This edition contains his first two “setts,” a total of 12 cotillions; courtesy of Kurt Stein Collection of Francis Johnson Sheet Music at the University of Pennsylvania]

The cotillion was a social dance instigated by French royalty. It became a huge trend in the United States during the early 1800s and the craze took over White and Black social gatherings of the time. The term cotillion, and later quadrille, can be synonymous with our present-day use of the term song as it was the most popular music style during that time.

Take a moment to listen to cotillion music written by Frank Johnson here.

In 1820, Johnson gave the family of Benjamin Rush, a well-known physician and signer of the Declaration of Independence, a manuscript of nearly 100 original cotillions. By the end of the 1820s, Johnson was the go-to person to hire for any cotillion ball, arguably the most popular musician in Philadelphia. His music became increasingly available in many of the city’s music stores.

[Cover Page of the Phoebe Rush manuscript at the Library Company of Philadelphia. The text reads: Presented to Mrs. A Rush by Frank Johnson, a Black musician of dance balls and parties, in 1820 – this [illegible] was one of much [illegible] and…]

Simultaneously, Johnson was the bandleader for Philadelphia’s military regiment the Washington Grays. In 1824 Johnson joined the First Troop Philadelphia City Cavalry for American Revolution war hero General Marquis de Lafayette’s tour of the northeast. Here, they led a two-mile march culminating at Independence Hall, a 5-minute walk from Johnson’s home on Pine between 5th and 6th. The Johnson band would then be invited as a musical act for a ball in Lafayette’s honor at the Chestnut Street Theater, across the street from Congress Hall at Chestnut and 6th (Jones 2006, 90-91).

[Cover page for Honor to the Brave: Lafayette’s March (Jones 1982, 75)]

He lived right on the corner of 6th and Pine. In fact, there is a historical marker dedicated to him on that spot.

1832 - A Trip to the South

Johnson’s connection to our country’s early history is seen again in 1832 when the Francis Johnson Band accompanied the Washington Grays to George Washington’s tomb in Mount Vernon, Virginia for the 100th anniversary of his birth. Here, the band played Johnson’s original composition for the event: Centennial Dirge.

[Johnson’s self-published Centennial Dirge; courtesy of the Clements Library at the University of Michigan]

The most interesting detail on the cover page of this music is at the bottom where it reads “Pub. & Sold by the Author.” This note underlines Johnson’s wealth, status, and the resources available to him.

This must have been a strange composition to write and a strange trip for Johnson and his band. George Washington was an enslaver and now Johnson was being asked to write music to honor him. Washington was well-known for circumventing Pennsylvania laws such that the enslaved people he bought with him to Philadelphia from the south, would not be able to become free. Oney Judge and Hercules were two enslaved people who most likely used connections in Philadelphia's Black community to self-liberate from George Washington. It's quite possible that Johnson knew this history.

Note that the Avenging the Ancestors Coalition ensured that we always remember the people that Washington enslaved in Philadelphia with this beautiful memorial at the Independence National Park.

There must also have been some trepidation for Johnson and his band to travel into the south. In Philadelphia they were celebrated musicians living as free men. But in the south, they might immediately lose all legal rights as free people upon crossing out of Pennsylvania.

Hundreds of people had been enslaved at Mount Vernon and still were when Johnson's band visited. I imagine this trip to Virginia was a culture shock for Johnson and his band, most of whom were born free in Philadelphia. This was likely the first time in their lives they directly saw the atrocities of human bondage, connecting the stories they must have heard from formerly enslaved people who moved to Philadelphia.

This composition serves as an important moment in African American history. By 1830, the enslaved population in the United States was over 2 million. This composition is an emphatic statement of just how highly regarded Johnson was despite the racist structure plaguing the nation. This moment mirrors Marian Anderson singing at the Lincoln Memorial despite being refused a space at Constitution Hall. A present-day example of comparable praise is Amanda Gorman's reading of her poem "The Hill We Climb" at the presidential inauguration in January 2021.

1837 - A Trip Overseas

In the fall of 1837, Johnson left James Hemmenway and Edward Augustus in charge of the band in Philadelphia as he took four members on a trip to Europe to further their musical abilities: William Appo, Aaron J. R. Connor, Edward Roland, and Francis Seymour.

Like Johnson, Hemmenway and Augustus appear on the 1838 census of Black Philadelphia. In this screenshot from the 1838 Census, you can see that James Hemmenway lived on 51 Pine Street, which was directly across from Headhouse Square. He listed himself as a hairdresser, even though he was an active musician. He most likely continued an additional occupation to support playing music.

Connor and Appo, whose older sister was married to Johnson, lived in the Johnson residence until the Johnson’s moved to 170 Pine by the following year. Appo moved to New York (see 1840 New York census) and Connor took up residence at 154 Pine until 1850 when he moved to 90 N. 9th St. (The North American, 22 March 1850).

In this ad, Johnson is telling his fans that he's leaving for Europe and that James Hemmenway and Edward Augustus will be in charge of the band until he returns.

[Johnson’s ad informing the public he will leave for Europe in The National Gazette on June 19, 1837; courtesy of newspapers.com]

They became the first Americans to travel to Europe as working musicians. The goal was to come back to Philadelphia with new music and increased musicality. After successful concerts in London and a possible trip to Paris, he returned stateside on May 14th, 1838, surpassing the goal he set out in his ad with great reception.

This was three days before the burning of Pennsylvania Hall. Racial tensions in Philadelphia had reached another apex when they returned, as on May 17th, 1838, the abolitionist crowd-funded public building “Pennsylvania Hall” burned down. Though he enjoyed success everywhere he performed, reminders of racial divisions in this country were always present in his career.

1838-1844 - Growth and Sacred Concerts

Johnson's band continued to perform in all types of venues in Philadelphia. This ad highlights Johnson's band as having an 'elegant selection' of new music from Europe.

[An ad posted in the Philadelphia Inquirer by Johnson on November 8, 1841 courtesy of newspapers.com]

By 1840, his musical engagements were as various as anyone in the world. He was a popular music composer, a respected military bandleader, a social dance music star, and an avid performer for the church; he debuted new instruments, cotillionized popular opera numbers, and wrote music dedicated to the public (firemen, mechanics [working class people], and food providers [butchers and drovers]) and major world leaders (George Washington, Queen Victoria, and Haiti’s second president Jean-Pierre Boyer). He even set out for an eight-month Grand American Tour from 1842-43, reaching the northeast, mid-west, deep south, and present-day Canada.

[First two programs, 1827 and 1833, respectively, scanned from Arthur R. LaBrew’s Studies in Nineteenth Century Afro-American Music; Third program is from March 20th, 1840, courtesy of Library Company of Philadelphia]

This concert of Black singers and musicians, which was first held in March of 1841 at First African Presbyterian Church, which was then at 7th and Bainbridge, was said to have 50 musicians, the size of a full orchestra (Southern 1977, 307). Note that the concert supported the Philadelphia Library Company. This was not the Library Company that we know of today - this was a Black Library Company that was said to have over 600 books in a library in the basement of St. Thomas' Episcopal church.

This program was so popular that it was repeated a few weeks later at St. Thomas Episcopal Church.

[Ad and program for a grand concert at St. Thomas; courtesy of Historical Society of Pennsylvania]

As successful as Johnson was in White social circles, he was active in the Black community, supporting abolition and giving to his community. In 1831, he was a contributor to the Benjamin Lundy Philanthropic Association, a Black organization that provided medical care and rental assistance to Freedom Seekers.

[Page from the Benjamin Lundy Philanthropic Association Order Book, courtesy Leon Gardiner Collection, Historical Society of Pennsylvania]

Two pieces of music demonstrate the depth of feeling he had about the plight of enslaved people. He penned the Recognition March of the Independence of Hayti, which was published in 1826. The Haitian revolution was incredibly violent. While most White people were against the revolution, most Black people in the diaspora celebrated the first Black independent republic in the world, and the ability of formerly enslaved Black people to defeat Napoleon.

In 1837, he set a poem called The Grave of the Slave to music. This poem, written by Sarah Forten, from the abolitionist Forten family, clearly describes the pain of enslaved people who lived and died without any recompense or recognition.

He used this new composition to close a sacred concert at St. Thomas Church.

[Ad for a Sacred Concert at St. Thomas Church from April 20, 1837; courtesy of newspapers.com]

I like this concert program a lot as it is a snapshot of how musical this community was. A popular large vocal work by my favorite European composer, Joseph Haydn, is the featured work on the program. After a grand showcase of the instrumental and vocal abilities of the church, they close with this powerfully solemn song created by Black Philadelphian artists.

I can see an all-Black choir and orchestra engaging in a large-scale rendition of this new song. For a more dramatic flair, I see Johnson with his bugle, embellishing those moments of music without words, flashing his excellence like a European concerto mixed with explorative improvisation we know today from jazz. As far as I know, no such rendition of this song has been recorded.

Passing from This World

Frank Johnson died on April 6, 1844. His funeral was held at St. Thomas Episcopal Church, which was then on Fifth street, just south of Independence Hall.

We suggest you play the following dirge as you read the funeral description.

The reporter described the funeral procession as "one of the most solemn we have ever witnessed". No one talked "but all walked slowly, seemingly absorbed in thought. "

At the grave site, the musicians, whose instruments were "shrouded in mourning" played a "parting dirge over his grave."

[Philadelphia Public Ledger, April 10, 1844; courtesy of Newspapers.com]

Frank Johnson's Legacy

The legacy of Francis Johnson has been largely omitted from music history since the beginning of the 1900s. While a resurgence of interest in his life and music is present today, there is more we can do to ensure his life is not forgotten again. There are few recordings of his published music currently available. I encourage all musicians to seek out his compositions and produce recordings of his music. As America’s first master of music, he deserves as great an archive of electronic recordings as any other composer.

Sources:

Jones, Charles K. Francis Johnson (1792-1844) : Chronicle of a Black Musician in Early Nineteenth-Century Philadelphia. Bethlehem: Lehigh University Press. 2006.

Jones, Charles K. and Greenwich II, Lorenzo K., “A choice collection of the works of Francis Johnson Vol. 1,” New York: Point Two Publications. 1982.

LaBrew, Arthur R. “Chapter III: The Underground Musical Traditions of Philadelphia, Pa. (1800-1900).” Studies in Nineteenth Century Afro-American Music. Detroit, Michigan [s.n.], 1983.

Southern, Eileen. Musical Practices in Black Churches of Philadelphia and New York, ca. 1800-1844. Journal of the American Musicological Society, 30(2), (1977): 296–312. https://doi.org/10.1525/jams.1977.30.2.03a00050

Southern, Eileen. The Music of Black Americans: A History. Third edition. New York, New York and London, England: W.W. Norton & Company, 1997.

Digital Archives and Libraries

HathiTrust Digital Library

Historical Society of Pennsylvania

Kurt Stein Collection of Francis Johnson Sheet Music at the University of Pennsylvania

Library Company of Philadelphia

Library of Congress

New York Public Library

William L. Clements Library at the University of Michigan