The Law In Her Pocket: A Look into Black Philadelphia's Struggles and Victories in Public Transit in the 19th Century

- 1838 Black Metropolis

- Aug 17, 2025

- 4 min read

Updated: Aug 18, 2025

Equality in public transit in Philadelphia begins with 19th Century Black Philadelphians who risked safety, livelihood, and reputation to claim a basic right: to ride.

1840s - Making Protest Public

The struggle started even before streetcars; with stagecoaches in the 1840s.

In November 1840, Westward Keeling, a formerly enslaved entrepreneur and Shiloh Baptist church builder, used the most public “platform” he had: the classifieds.

When a stagecoach refused to seat his 14-year-old daughter Araminta inside; she was forced to ride on top, in the cold, from West Philadelphia to Lombard street.

Keeling published a blistering ad asking the city how it could accept such treatment of a child.

Decades later, he was still organizing meetings to protest trolley discrimination. The paper trail he left shows how ordinary people made public space a battleground long before the Civil War.

1860s - Fighting Through Consistent Humiliation

The stakes were life and death. In November 1862, Rev. Richard Robinson, an elder AME minister who had served at Mother Bethel and traveled to Haiti in the 1820s, was denied a seat and made to stand on the streetcar’s exposed front platform during a storm.

The car collided with a hay wagon; Robinson later died of his injuries.

Black leaders, meeting through the Social, Civil and Statistical Association (SCSA), rallied legal aid for his family and pressed the larger fight to end transit segregation. His death became a martyr’s marker in the campaign.

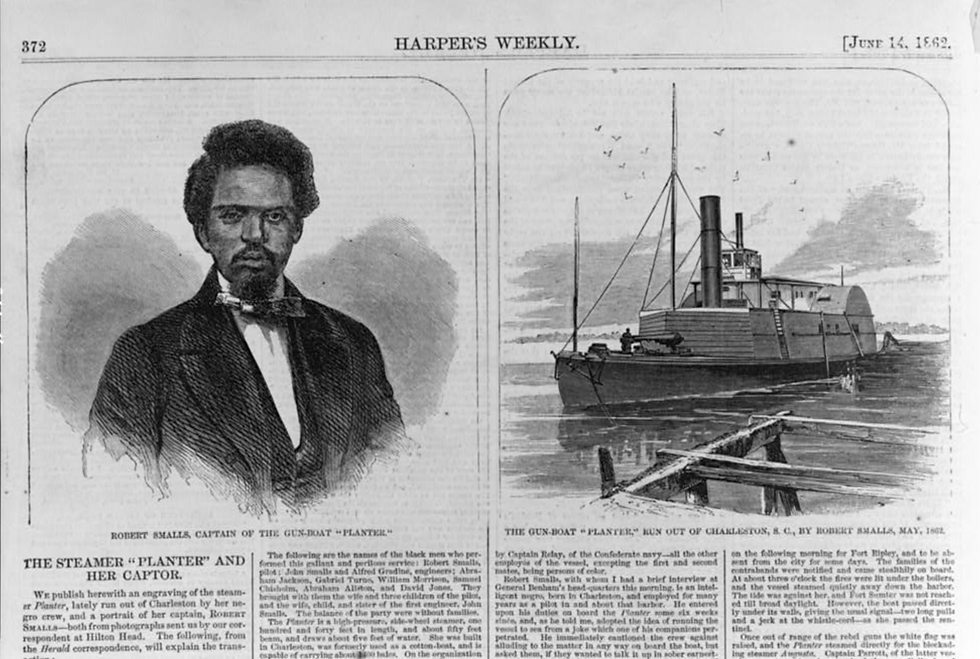

Even national heroes touched Philadelphia’s transit fight. In 1864, Robert Smalls; the Civil War legend who commandeered the Confederate steamer Planter to freedom; was humiliated on a Philadelphia streetcar.

This must have been so incredibly demoralizing. To have returned from the war as a lauded hero only to not have the basic right to ride the trolley.

By 1866, we can hear the echos of frustration in this public lecture at the Banneker Institute, a Black intellectual society, where the topic was "Has the war for Human Freedom been fought in vain?"

Fighting systemic inequity can be exhausting. And often it is most difficult right before major victories. How does one pick oneself up from this type of humiliation?

Late 1860s - Persistence Breaks Through

Evidently, our ancestors dug deep and kept pushing. Because, by the late 1860s, the movement had coalesced.

Educator and activist Caroline LeCount - Institute for Colored Youth graduate, principal of the Ohio Street School - joined other Black women like Mary Miles and Mrs. Derry in protest actions. Organized by the Pennsylvania Equal Rights League, led by Octavius Catto and Jacob C. White Jr., this tactical campaign went like this: board the cars, refuse ejection, bring the cases to court and the press, and lobby Harrisburg and Washington.

If this sounds familiar, like maybe something you heard in the 1950s civil rights movements - 100 years later - note that many 'textbook' civil rights actions were first practiced in Philadelphia's Black Metropolis in the early and mid 1800s.

Their persistence worked.

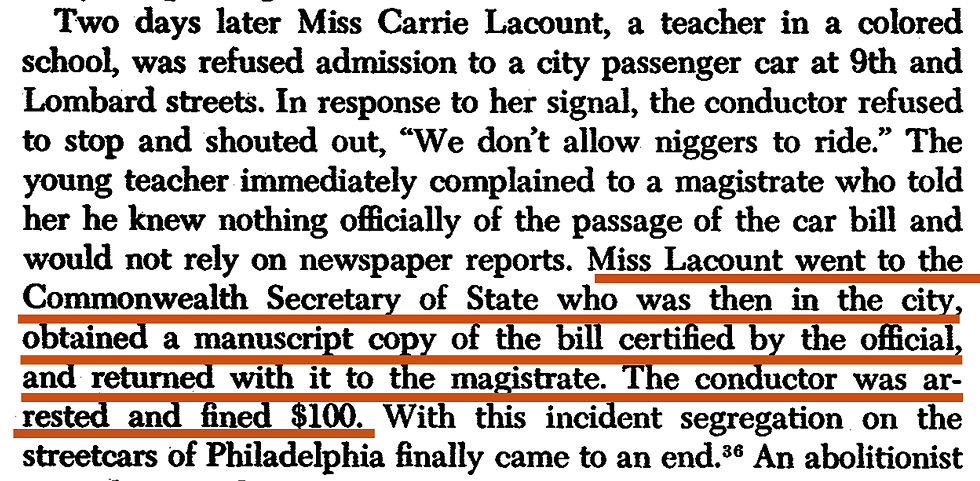

On March 22, 1867, Governor John W. Geary signed a state law banning racial discrimination on Pennsylvania streetcars.

Days later LeCount enforced it herself, having a streetcar driver arrested when he refused her a ride; an early example of civil-rights enforcement from the ground.

Carrie LeCount went to get the law, put it in her pocket, then went back to show it to the magistrate to have the conductor arrested. She bought it out at the right time and ensured it's enforcement.

We can certainly do the same.

Following In Their Footsteps

What do we do with this history now? We remember that Philly’s transit rights were won by neighbors, ordinary people, who refused to accept second-class status; by a father with a newspaper ad, by a minister who paid with his life, by a school principal who carried a copy of the law in her pocket.

This tradition of public protest - and this history of victories - should not be forgotten. It stretches from the 1840s through the Philadelphia Trolley Car strike of the 1940s and to us today.

Persistence until success - public comment, rider councils, board meetings, union listening sessions, data-driven testimony, keeping the law in your pocket - is our inheritance.

And it worked. Let your voice be known.

Sources

Key Source: Go deep into the details with Phil Foner's articles - The Battle to End Discrimination Against Negroes on Philadelphia Streetcars: (Part I) Background and Beginning of the Battle https://journals.psu.edu/phj/article/view/23726/23495

and The Battle to End Discrimination Against Negroes on Philadelphia Streetcars: (Part II) The Victory https://journals.psu.edu/phj/article/view/23743/23512

1838 Black Metropolis: “Westward Keeling; an 1840s activist living an extraordinary ordinary life.” https://www.1838blackmetropolis.com/post/westward-keeling-an-1840s-activist-living-an-extraordinary-ordinary-life

1838 Black Metropolis: “The Gibbs Brothers Run the World.” https://www.1838blackmetropolis.com/post/the-gibbs-brothers-run-the-world

Villanova University Digital Library; Institute for Colored Youth: “Caroline LeCount Bio.” https://exhibits.library.villanova.edu/institute-colored-youth/graduates/caroline-lecount-bio

Steven J. Ramold, Black Troops, White Commanders, and Freedmen During the Civil War https://www.google.com/books/edition/Black_Troops_White_Commanders_and_Freedm/x-niVYahYfUC?hl=en&gbpv=1&bsq=84

Harper's Weekly, May 1862. "Robert Smalls, captain of the gun-boat "Planter" The gun-boat "Planter," run out of Charleston, S.C."

Catto.UsHistory.org Chapter 5: Streetcars