A Procession of Unified Purpose: The Day the Philadelphia Black Metropolis Announced Its Power

- 1838 Black Metropolis

- Dec 17, 2025

- 13 min read

Updated: Jan 15

On April 26, 1870, Philadelphia witnessed a Black voting rights parade so large, so proud, and so exquisitely organized that it most likely changed the course of the 1871 mayoral election.

Five hours long, thousands of people deep, nearly matching the scale of a Mummer’s Parade. The parade started on Broad, wound through the city, passed by Independence Hall, and ended with a catered gala at Horticultural hall, back on Broad.

And the day concluded with a pyrotechnics display.

It was a celebration of the Fifteenth Amendment, which changed the US Constitution to say "The right of citizens of the United States to vote shall not be denied or abridged by the United States or by any State on account of race, color, or previous condition of servitude."

This was a joyous occasion for a Black community that had never stopped fighting for suffrage since it was lost in 1838.

But it was also something far more strategic.

This parade was a political masterclass engineered by Octavius Catto, Isaiah C. Wears and a network of Black organizers who understood that thousands of newly enfranchised Black men needed to be ready to vote immediately.

The parade was both spectacle and civic education, a joyful explosion and a calculated exercise in political power.

The Challenge

To understand the brilliance of what these organizers accomplished, you have to place yourself in the shoes of a Black man in Philadelphia in 1870.

Imagine you volunteered for the United States Colored Troops during the Civil War. You fought bravely. You returned home in 1865 with injuries. And in Philadelphia, your home city, you still could not ride the trolley. You still could not vote.

Then, suddenly, in February 1870, the Fifteenth Amendment passes. Black Philadelphia leaders were part and parcel of that passage - including Isaiah C. Wears who was invited to Washington to help draft it.

And now, for the first time in your life, you have the legal right to vote.

But you have no roadmap. No experience with wards and the actual exercise of going to a poll to vote. Your social world is made up of benevolent societies, churches, lodges and mutual aid groups. Politics certainly is a part of all these groups but the physicality of voting had never been part of your lived experience.

Overnight you're expected to step into a new civic role, and to do it properly, you'll need some guidance.

Now imagine you are Octavius Catto and Isaiah Wears, sitting at the Pennsylvania Equal Rights League office at 7th and Lombard, on a cold, snowy winter evening in February, realizing that 9,000 Black men in this city are suddenly eligible to vote and have no idea how to begin.

And you know what is coming.

The 1871 mayoral election. A machinery of white supremacist Democrats running city government, police and fire. A political environment hostile to Black votes and prepared to suppress them.

If Black men could be organized, truly organized, they could change the outcome of that election and usher in leaders aligned with civil rights.

Catto, Wears, David Bustill Bowser, William Still and many others knew exactly what was at stake.

Meeting the Moment Via a Parade

The Pennsylvania State Equal Rights League had already been advocating for 15th amendment celebrations and many localities had decided on a parade. The Philadelphia leadership followed suit.

And so they turned to the strength that defined Black Philadelphia - the astonishing organizational juggernaut that was the Philadelphia Black Metropolis. This city-within-a-city had organized it's own municipal, educational, theological,, social, financial and emancipation infrastructure for the past century.

Using these networks, the question was now, what was the quickest and easiest way to get thousands of Black men trained and ready, knowing which ward they belonged to, understanding their rights at the polls, and being clear on the physical actions of voting - from knowing your candidate to casting your ballot?

The Genius of Organizing by Ward

One of the most brilliant decisions the organizers made was deceptively simple; organize the parade by ward instead of by existing social groups.

This mattered because Black Philadelphians already had robust organizations. It would have been easier to base the parade on those structures.

Instead, they introduced Black men to a new social identity; the ward.

For newly enfranchised men, marching in ward formation created new networks of voting support. It taught who belonged together politically. It made the abstract structure of city politics legible and physical. It showed men exactly where they would stand when they went to vote.

Importantly, the critical function of voting instruction and know-how would continue to be shared among them and through the new ward networks.

And to the rest of Philadelphia, the message was unmistakable,

Black voters were organized by political unit, disciplined, visible and ready.

Reading the Messages

The parade sent messages on multiple levels, through the order of marchers, through banners and portraits, through symbolic floats and through the sheer number of bodies moving through the city.

Nothing was accidental.

This parade was designed to be read.

The Procession

First, the procession was organized into units that broadcast symbols of American citizenship; military brigades, political wards and labor organizations.

At the front of the parade were the veterans, the 27th Post of the Grand Army of the Republic. This was 500 men, former Colored Troops in their Civil War regalia. They were followed by the orphans of veterans. Both of these groups messaged the sacrifice that Black people had already made for the Union.

Interspersed throughout were notable individuals, including Frederick Douglass, in individual barouches, waving to the crowd. Douglass came early in the parade.

Then, labor and political organizations. The Coachmen’s Society turned out more than 200 men on horseback, all dressed alike in black suits and white caps.

They were followed by 400 men in the Hod Carriers and Laborers Association, marching in formation. They were also in uniform, wearing red shirts, black pants and fatigue caps. They carried an American flag and a banner with a picture of General Grant with the inscription: “Our Choice for President in 1872.”

Note that by this point, 1000 Black men had already marched. And this is just the beginning of the parade.

Political organizations like the Catto Equal Rights League of Bridgeton New Jersey and the New York Club showed a national network of Black political power, were next.

The Thaddeus Stevens Monumental Association must have been quite a sight. The press reports that they “turned out in full force.” They were dressed in black suits, high hats and white gloves. Their banner had a Cuban flag.

And then, the wards.

Given that there were approximately 9000 Black men in Philadelphia who were now eligible to vote, we can make a rough estimate that about 2/3rds of them marched in the parade. This would give us about 6000 participants within the wards.

And between each ward were bands, many of them made up of white musicians.

Taken together this procession communicated legitimacy and discipline. This was not about individuality. It was about collectives of people, dressed alike, moving alike, united towards political outcomes, proudly proclaiming political preferences, like “Grant, Our choice for President”, and international Black alliances, like the Cuban flag.

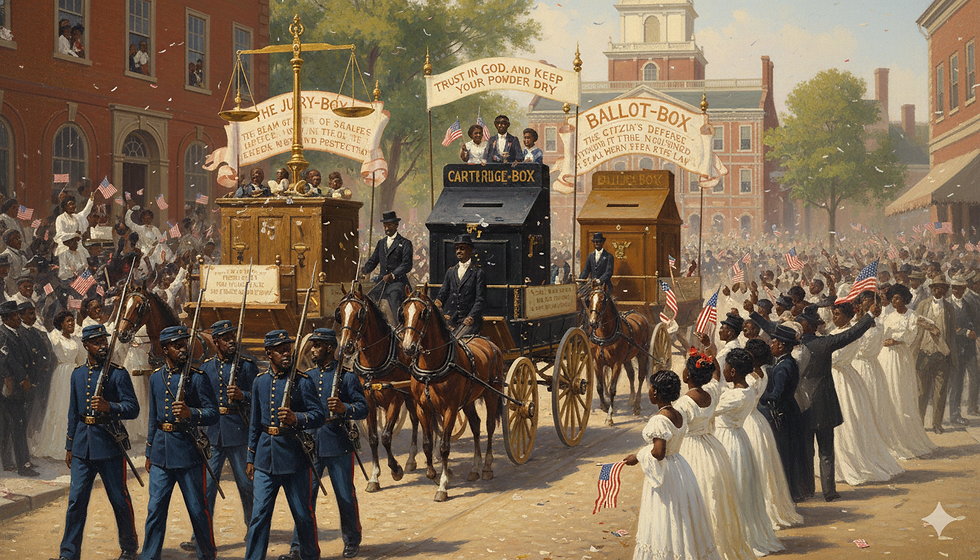

The Floats

Second, the parade wagons carried messages that could be read symbolically.

For example, the Fifth Ward, the ward of the highest Black population in the city, created a mobile exhibit of three wagons in a row that played with the idea of the various kinds of boxes in the American context and their role in this new political environment.

The first wagon carried a Jury Box. This was a wooden jury box mounted on a wagon, crowned by the beam of the scales of justice. Banners on either side of the wagon read:

“The Jury Box, the beam of the scales of justice and the citizen’s rights and protection.”

“The Jury Box, the wisdom of God hath not devised a happier institution than that of juries.”

The second wagon carried a large ballot box that was painted black and revolved. The name of the wagon was “Cartridge Box,” which is a box where one would keep ammunition for guns. By painting the ballot box black, this display merged the meaning of the ballot box and the cartridge box. Banners on either side of the wagon read:

“Cartridge Box, the nation’s protection. Trust in God, and keep your powder dry.”

“Cartridge Box, the medicine chest from which the nation drew the panacea for the cure of the Rebellion.”

The third wagon was “The Ballot Box.” This carried a simple ballot box with the messages:

“Ballot Box the citizen’s defense: through it the nation is governed, and by it all men are equal in law.”

“Ballot Box, the citizen’s protection against encroachments of fraud, injustice and oppression.”

There are multiple ways to interpret this set of mobile exhibits. Here are just a few.

The jury box represents justice. You place your peers into that box to protect your rights within the judicial system. It also introduces the idea that as citizens, Black men would now serve in juries, representing a layer of protection and power that had not occurred prior to the 15th amendment.

The cartridge box is where you place ammunition for your gun. It represents self protection and action. Paired with the banners urging vigilance, like “Keep your powder dry,” and efficacy, like “cure of the rebellion,” it communicates the ability and knowledge that power lies in the ability to turn to armed defense of position if necessary.

The ballot box revolving and made to look like a cartridge box indicates a transfer of power from armed defense to political defense. It says to Black men who just fought in the Civil War that they should transfer their ability to self protect from armaments to political action, while warning to not completely drop the protection of arms, even harkening the legitimacy of armed protection during the Civil War.

And then there is finally the Ballot Box.

By this point, two familiar boxes have been established. Boxes that already exist in society. Boxes that Black men understood, even if they had been excluded from full participation in them. Now a third box is introduced.

The ballot box gains its meaning from the first two. Justice. Protection. And now finally, the vote. The ballot box becomes the next form of protection. A nonviolent armament. A way to safeguard rights, like “the citizen’s protection against encouragements of fraud, injustice and oppression,” without resorting to the cartridge box.

If someone came to the parade without understanding the ballot box, they could walk away from this visual symbolism, ensconced in multiple layers of meaning, with the firm understanding that the ballot box was phenomenally important.

The Serenade: A Flex in Sound

And then there is one more moment from this parade that we absolutely have to talk about, because it was a flex in its own right.

As the procession moved up Fifth Street, a delegation peeled off and stopped in front of Mayor Daniel Fox’s house. Fox, remember, was the white supremacist in chief. His administration shaped the very police force, aldermen and civic machinery that would go on to terrorize Black voters in 1871. This was not a friendly mayor. This was not a neutral mayor. This was a mayor whose political power depended on suppressing the very people marching.

So what did the marchers do?

They serenaded him.

A deliberate halt. A unified body. And then a song lifted up toward his windows.

The mayor himself wasn’t home, but his family stood there watching thousands of Black Philadelphians pass in disciplined formation, accompanied by a delegation that planted itself right at their door and sent up what the papers politely called “a compliment,” but which we should be honest about. This was a vocal thunderclap.

A thunderous sound aimed directly at the symbolic center of white political power.

The Banners

Finally, the banners held aloft above the marchers intentionally communicated political preferences, liberation theology, and historical justice.

The twelfth ward had a banner with a portrait of Samuel Williams with the message “We Remember Christiana.” Christiana was an 1851 resistance movement where the Black community in Christiana successfully took up arms against slave catchers emboldened by the 1850 Fugitive Slave Law. Thirty eight leaders of this resistance movement, including Samuel Williams, who was sent by William Still to spy on slave catchers, were tried for treason and they all were acquitted. This event has been described as the “first battle of the Civil War.”

This parade was twenty years after that event. Remembering Christiana is an act of Black historiography. Those who may have forgotten are encouraged to recall the event via the banner. More, it messages that the Black community remembers its intellectual genealogy in self protection against unjust laws.

Echoing this liberation theme, the fifth ward carried a banner aloft proclaiming “Equality, Resistance to tyranny is obedience to God,” moving liberation into the realm of theology.

Similarly the Young Men’s Vigilant Association, whose banners in the 1842 Temperance Parade that led to the Lombard Street mob attack were famously torn down during that attack, also came with a message of Black liberation genealogy.

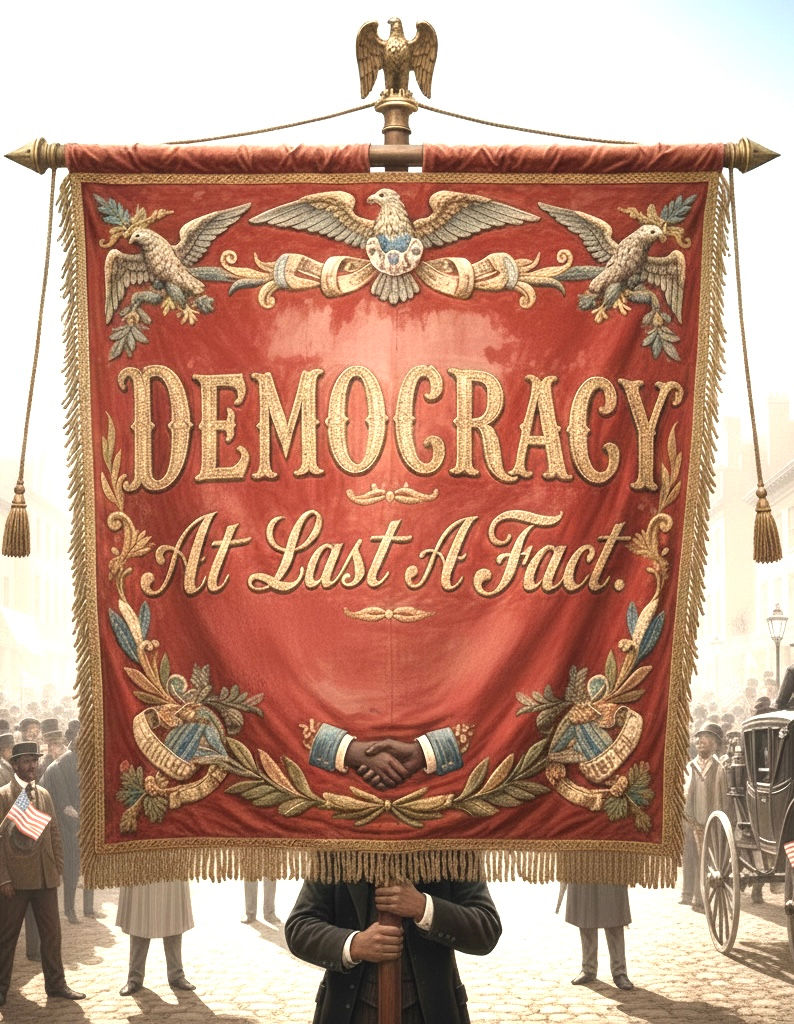

Their banners read “We stand by those who stood by us, Petersburg, Richmond, Fort Fisher.” These were all decisive Civil War battles where Colored Troops played an important role.

Bringing a sense of irony to the parade they also carried a banner that said “The Declaration of Independence, At Last A Fact.”

We encourage you to read all the messages in the banners in this article and this one.

Putting It All Together

When you put all of this together, the ward structure, the disciplined marching, the national alliances, the military regalia, the labor organizations, the floats that taught civic meaning, the theological assertions, the Civil War memory work, the presence of Frederick Douglass and the thousands of Black men moving through their city with pride and purpose, you begin to see the true scale of what this parade accomplished.

It was not just a celebration.

It was political education.

It was a show of force.

It was a declaration of readiness.

It was a transformation of Black men into voters, jurors, civic participants and political agents.

And it sent a message to the entire city, Black Philadelphia was organized, strategic, disciplined, intellectually rigorous, spiritually grounded and fully prepared to wield political power.

The ripples of that day traveled straight into the 1871 election, straight into the conflicts that cost Catto his life and straight into the political landscape we inherit today.

Because in April 1870, the Philadelphia Black Metropolis did not simply enter American democracy, it marched into it, brilliantly, boldly and together.

PostScript:

The country as a whole decided to celebrate the passing of the 15th Amendment with more parades on May 19, 1870. There are lithographs from these major parades that give an idea of what this parade may have looked like. Our lithograph visuals are from these sources (see below).

There's also so much more to this story - there's all speeches at the churches, the presentation of a banner by the Union League, more banner messages, more floats - it was incredible. We encourage you to continue reading this article and this one..

Estimating the Size of the Parade

To estimate the size of the 1870 Fifteenth Amendment parade, we began with the 1870 census count of 22,147 Black residents in Philadelphia and 9025 Black men. From there, we assumed that not all eligible men would participate in the parade due to age, work obligations, illness, or access, and estimated that roughly 2/3rd took part as ward-based marchers, yielding a working estimate of about 6,000 ward marchers.

This figure represents only the men marching by ward, the core political formation of the parade. It does not include additional participants who marched outside of ward structure, including military units like the 27th Post of the Grand Army of the Republic (approximately 500 men), labor organizations such as the Hod Carriers and Laborers Association (around 400 men) and the Coachmen’s Society (about 200 men on horseback), or guest delegations from New York, New Jersey, and other cities. Taken together, these clearly documented groups suggest that the total number of marchers exceeded the ward count alone, reinforcing contemporary descriptions of the parade as a mass political mobilization on the scale of several thousand participants.

Sources:

A list of all newspapers references to 15th amendment organizing meetings held during March and April.

1838 Black Metropolis, the 1842 "Lombard Street" Mob Attack https://storymaps.arcgis.com/stories/acf474893636438c98b359805d2add8d

1838 Black Metropolis, Election Day 1871, A Timeline of Events: https://storymaps.arcgis.com/stories/972b462eec744978b610e90e64031a26

Biddle, Daniel R., and Murray Dubin. Tasting Freedom: Octavius Catto and the Battle for Equality in Civil War America. Temple University Press, 2010., https://archive.org/details/tastingfreedomoc0000bidd/page/490/mode/2up

"Celebration Parade by the Black community for the passage of the 15th Amendment" Newspapers.com, The Philadelphia Inquirer, April 27, 1870, https://www.newspapers.com/article/the-philadelphia-inquirer-celebration-pa/186608894/

Celebration in honor of the ratification of the fifteenth constitutional amendment, on Tuesday, April 26th, 1870, Philadelphia. (1870). https://id.lib.harvard.edu/alma/990031736730203941/catalog

"Joyous Celebrations of Enfranchisement in the Black Metropolis" Newspapers.com, The Evening Telegraph, April 26, 1870, https://www.newspapers.com/article/the-evening-telegraph-joyous-celebration/186528626/

Metcalf & Clark (Firm). "The result of the Fifteenth Amendment, and the rise and progress of the African Race in America and its final accomplishment, and celebration on May 19th A.D. 1870." Print. Baltimore: Metcalf & Clark, 1870. Norman B. Leventhal Map & Education Center, https://collections.leventhalmap.org/search/commonwealth:q524n5781

"Prep meeting for the 15th Amendment parade in the 14th ward, lead by Isaiah C. Wears" Newspapers.com, The Philadelphia Inquirer, March 11, 1870, https://www.newspapers.com/article/the-philadelphia-inquirer-prep-meeting-f/187265943/

The Fifteenth Amendment. Celebrated May 19th 1870. From an original design by James C. Beard. The Library Company of Philadelphia. https://digital.librarycompany.org/islandora/object/Islandora%3A65085

Schreiber, George Francis, photographer. Frederick Douglass, head-and-shoulders portrait, facing right. [Philadelphia, 26 April] Photograph. Retrieved from the Library of Congress, www.loc.gov/item/2004671911

Silcox, Harry C. Philadelphia Politics from the Bottom Up: The Life of Irishman William McMullen, 1824-1901. Balch Institute Press, 1989. https://archive.org/details/philadelphiapoli0000silc/page/68/mode/2up